“In addition to the technical knowledge provided by this special course, it is necessary to count: 1. A training towards more agility in the overall drawing - 2. A training to paint synthetically, by large parties of shadow and light, two things absolutely necessary, difficult to acquire, and that in almost all painters is lacking”

Extract from André Lhote’s teaching programme - André Lhote Archives

1921. Elena Popea’s work is on the cusp of what her biographer Maria Dumitrescu considers her artistic maturity. In February of that year, she takes part in the “Collegium Artificum Transylvanticorum”, an exhibition organised in Cluj-Napoca by the Austro-Hungarian-born Romanian poet Emil Isac (1886-1954) and aimed at bringing together for the first time the finest Transylvanian artists of the time. Her work is noticed: the eminent Romanian art historian Coriolan Petranu (1893-1945) describes her as one of “the two outstanding personalities” of the event. In April, she presents her work at the yearly exhibition of the “Tinerimea artisică” (The Artistic Youth) in Bucharest. In the following years, she exhibits regularly in Romania and France.

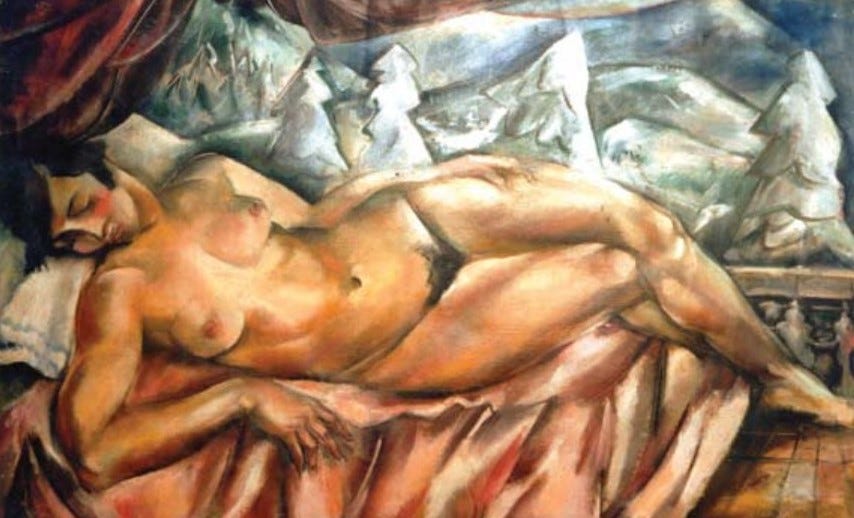

While in Paris in 1922, she seeks out André Lhote (1885-1962), an influential Cubist painter and art critic. At the time, he is teaching at the Montparnasse Academy, where Popea starts following his classes. Under his guidance, she turns her attention to matters of form and geometric construction, in which perspective is distorted or abandoned ; she sharpens her colours and defines her brushstroke ; her painting gains in strength, clarity, and individual expression. See for instance her Nude – in all likelihood a study for one of Lhote’s classes -, in which she portrays the model stretched across a bed, red draping brushing along the floor and hanging above a winter decor of snow-covered pine trees. There is a clear separation between the bed and the background, defined by a small fence on the right. In the foreground, the warm tones of the draping and the model’s tanned skin dominate, whereas the background is depicted in cold blue and white hues. And yet, both foreground and background echo each other, through the curves of the lying woman and the outline of the fictitious hills, through the white pillow which blends into the landscape. The model’s head hangs to the side and her eyes are shut: where does she go to, when she is alone in her bed? Does she sleep or merely rest? Is the snowy landscape but an echo of the images of her own mind?

Elena Popea, Nude, oil on canvas, The Museum of Bucharest, Romania.

*

It is a rainy afternoon in Bordeaux – a day of intermittent showers and sad clouds. The murky waters of the Gironde River, full to the brim after weeks of wet weather, mirror the sunless sky, and seagulls flit back and forth across the turbulent surface where swirls and wavelets hint to a secret struggle between the natural flow of the river and the powerful push of the incoming tide. Just a few days ago, I was sitting by Lough Derg, in the North of Ireland, lost in thought as I gazed at the glassy surface of the lake. Shimmering water under a grey sky – constant ripples teasing the rocks by the shore – and out there, just a few hundred meters away, a long flat building: Saint Patrick’s Purgatory, a site of pilgrimage, seemingly floating on the water like a lacustrine mirage. Further along the lake, there is a well dedicated to Saint Brigid, who with Saint Patrick watches over Ireland through her patronage. We ambled along the path for a while – a while too short. We ran out of time and turned back before the well. A pleasant walk, then, and nothing more.

Mainie Jellett, The Virigin of Éire, c. 1943, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin.

About the same time Elena Popea started attending André Lhote’s classes, two Irish women approached him. They too were looking for new sources of inspiration and seeking training with the renowned teacher. André Lhote’s artistic approach and teaching methods were immensely popular amongst the young foreign artists – many of whom were women – who came to Paris to hone their artistic skills in the cultural capital. Many of them went on to carry his teachings abroad and introduce modernist painting in their home-country, such as those inseparable friends and talented artists, Evie Hone (1894-1955) and Mainie Jellett (1897-1944). His abundant correspondence and his personal archives testify to the cosmopolitan ambiance of his studio, his students’ eagerness in attending his classes, and the friendly relations he entertained with them. I wonder whose path Elena Popea crossed? Did she ever meet Evie Hone and Mainie Jellett in Lhote’s studio or in the bustling streets of the Montparnasse neighbourhood? And what would they have had to say to each other?

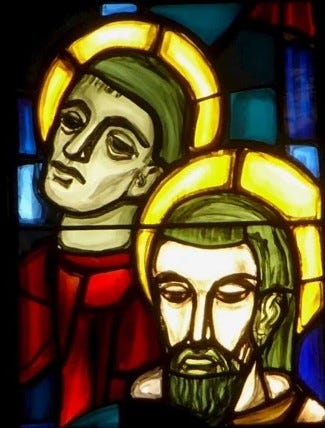

Hone and Jellett eventually left Lhote’s academy to study with Albert Gleizes (1881-1953), a French painter and theoretician, who published with Jean Metzinger the first essay on cubism in 1912. Perhaps Evie Hone was drawn to Gleizes’ more transcendental understanding of art – perhaps she felt the urge to somehow express the divine through her work. She spent two years in an Anglican convent, hoping to take her vows, realised she did not have a vocation, and eventually converted to Catholicism, to Mainie Jellett’s delight. After her time in Paris and her Cubist experiments, she returned to a purely figurative form of art through stained glass, joining in 1933 the An Túr Gloine stained glass studio in Dublin. Gleizes, too, experienced a slow conversion over the course of several decades, eventually taking his first communion in the Catholic church in 1941, at the age of sixty.

*

Evie Hone Mainie Jellett, Heads of Two Apostles, c. 1952, stained glass, National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin.

The two Apostles which now hang in the National Gallery of Ireland seem lost in thought, their eyes downcast, their lips clasped shut. One can only imagine what inner spiritual turmoil their placid countenances hide. Their bright yellow halloes shimmer in the dark room just as, now, the sun pierces through the drab clouds. I am sitting in a café in Bordeaux, peering at the Gironde through the window. Above me hangs a yellow neon sign, a childish smiley face. There has been a steady flow of customers as I have been sitting here quietly, reminiscing about my recent trip to Ireland and pondering over the dense web of artistic creation in Europe – evermore intricate as I follow in the steps of travelling artists. The barista walks up to me, they are closing shortly. And so I pack my belongings, tidy my thoughts, and leave Evie and Mainie and Elena to their artistic peregrinations.

Until I meet them again.

Further reading

Maria Dumitrescu, Elena Popea, Editions Meridiane, Bucarest, 1969.

Zeynep Kuban, Simone Wille (eds.), André Lhote and his International students, Innsbruck University Press, Innsbruck, 2020.

National Gallery of Ireland, “Irish Women Artists from the Archives” : https://www.nationalgallery.ie/what-we-do/library-and-archives/irish-women-artists

Peter Brooke’s blog and his article “Cubism and Tradition. The Liturgical art of Albert Gleizes and his school” : http://www.peterbrooke.org/form-and-history/tradition/

Previously on The Peripatetic Museum

In her footsteps...

“She travelled a lot, she rushed to achieve everything her vibrant temperament dictated. Her life was led with a constant inner burning, between successes and disappointments, travelling or in quiet rest in her studio in Bran…” Coriolan Munteanu, “Elena Popea”,

Je suis curieuse de si tu écrivais dans le café ou si tu as retranscrit plus tard le fil de tes pensées. C’est la magie de tes mots qui fait oublier le média pour laisser place aux sensations ☀️

Thank you for taking us along with you on your journeys, and for bringing the context of these paintings to life! I can't wait for your next piece 🥰