Two young children playing in the foreground; a woman in a red dress, draped in a yellow scarf and leaning on a pedestal on which a book lies open; and to the left, a man sitting in profile, sketching or writing. In the background, deep green foliage, a lake and a temple. It is this peaceful family portrait set in the Villa Borghese in Rome which opens the exhibition Louis Gauffier’s Journey to Italy, presented at the Musée Fabre (Montpellier) this summer.

Louis and Pauline Gauffier, Portrait de la famille Gauffier, 1793, oil on canvas, Uffizi Gallery, Florence.

The exhibition offers a striking retrospective of the French neoclassical painter Louis Gauffier (1762-1801), who first went to Italy after winning the Prix de Rome in 1784 (which allowed him to study for four years at the Académie de France in Rome). In 1793, following political unrest in the wake of the French Revolution, he left the Eternal City and moved to Florence, where he died a few years later, at the young age of 39.

However, this family portrait offers a more intimate tale of his life. Looking more closely, one notices differences in brushstroke between the man and the woman. Compare the details in the hands, face, and clothing of the woman with the much simpler profile of the man. This is because Louis Gauffier was not the sole artist behind the painting. He painted it with his wife, the artist Pauline Gauffier, née Châtillon, a former student of his whom he married in 1790. They shared a short life together, since she died a few months before him in 1801, but one which evidently included artistic partnership. I can just imagine them working together on this painting, posing for each other, sharing in all the concentration, hard work, and joy which is involved in artistic creation. Art which is done hand in hand, two minds sharing one canvas.

Opening with this unique family portrait, the exhibition also goes on to illustrate the difficulties involved in establishing a historiography of women artists - quite beside the difficulties they would have encountered during their lives. There are a mere handful of known paintings by Pauline Gauffier (two of which can be seen in the Musée Magnin in Dijon), and the Musée Fabre was only able to buy and exhibit one. It is a genre painting of a woman chasing a cat out of the window. In this instance, her name had been scratched off at some point in time, simply leaving her surname “Gauffier” - thus misleading a potential buyer on the actual authorship of the painting. The Musée Fabre, though, saw through this ploy.

Pauline Gauffier, L’Oiseau volé, ca. 1790-1800, oil on canvas, Musée Fabre, Montpellier.

Hence, through this acquisition, the museum not only introduced one of Pauline Gauffier’s paintings into its permanent collection, it also re-attributed it to her. She was recognised as a painter and her work was exhibited to the public. Pierre Stépanoff, co-curator of the exhibition, underlined in our discussion how important it was for women artists to enter collections and be shown in permanent exhibitions - out of historical accuracy, if nothing else. Far from an ideological perspective, he argued the great number of talented women artists during the first half of the 19th century justified their increased presence in collections, which still present to this day a biased - if not false - view of artistic creation during that period.

But Louis and Pauline Gauffier also illustrate how artistic couples can challenge the traditional dichotomy of male/female, artist/model, agent/object, and open stimulating perspectives on artistic creation, shared within a romantic relationship.

***

The exhibition at the Musée Fabre, the discussion with Pierre Stépanoff, as well as the previous visit of the Musée de Lodève (where I learnt about the sculptor Paul Dardé) naturally led me to Italy… Since Thursday, I have been making my way to Florence, in the footsteps of Pauline and Louis Gauffier. I will be arriving later today - if everything goes well. On the long and winding way there*, I stopped in Genoa and visited the Musei di Strada Nuova. (*I have been making it winding. After Genoa, I stopped over in the coastal town of Chiavari and in the Tuscan village of Bagnone.)

The Musei di Strada Nuova is in fact composed of three museums, housed in the Palazzo Rosso, the Palazzo Bianco, and the Palazzo Tursi, all located along the Via Garibaldi. In the Palazzo Bianco, one painting in particular stood out, and upon inquiry, it offered an eloquent echo to Louis and Pauline’s story : it was Simon Vouet’s David with the Head of Goliath (ca. 1620-1622). Simon Vouet (1590-1649) was another French painter who ended up in Italy, although he was there nearly two centuries earlier, and he returned to France in 1627, where he was appointed First painter to the King. And he was also yet another painter who married an accomplished artist in her own right : Virginia Vezzi. Little is known of her, but she was talented enough to become a member of the prestigious Academia di San Luca, a remarkable achievement considering her young age and her gender.

Simon Vouet, Davide con la testa di Golia, ca. 1620-1622, oil on canvas, Musei di Strada Nuova - Palazzo Bianco, Genoa.

And yet, only one painting is definitely attributed to her : Judith with the Head of Holofernes (ca. 1624-1626, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nantes) - the pair of them definitely had something with decapitated heads… (I would love to see both paintings side by side by the way, can this be arranged ?) She followed her husband to France, and was admired at the court of Louis XIII, described in the words of French scholar Isaac Bullart as “a Roman lady of singular beauty, and so well instructed in the art of painting that she often had the honor of working in the presence of the King and receiving from his lips words of praise for the works of her beautiful hand.” But little is known of her artistic career since. So where has all her artwork gone ?

Undeniably, tracing, documenting and buying women artists remains a challenge for fine arts museums. It requires curiosity and dedication on the part of curators, and the support of institutions to buy their art. As for the visitor, the existence of women artists still often has to be guessed at through hints and indirect mention of them in permanent exhibitions. If their art isn’t in museum collections, where is it ? Art is meant to be shown and seen, after all. If a painting has never been seen, does it even exist ?

And then again, each period has its challenges. During my brief stay in Genoa, I also visited the temporary exhibition on Tina Modotti (1896-1942) at the Palazzo Ducale: Tina Modotti. Donna, Messico e Libertà. Actress, photographer, and communist activist, she was born in Italy, emigrated to the United States in 1913, moved to Mexico in 1922, was exiled in 1930, was sent to Europe where she went to Russia, went to Spain during the Civil War, and finally returned to Mexico under a pseudonym in 1939. She died three years later.

Her life was one of passion and dedication, and from the picture the exhibition painted of her, she seems to have led meaningful romantic relationships whilst always maintaining her creative and personal independence. The challenges she rose to and the obstacles she overcame - most notably her exile from Mexico - appear more directly linked to her political activism rather than her gender (however, the smear campaign directed against her after the assassination of her partner Julio Antonino Mella focused heavily on her sexuality and her morals). Although the exhibition describes her as “donna”, “attivista” would have seemed perhaps more appropriate.

For her though, the struggle lay elsewhere, as she sought to balance her life and her art. As she wrote in 1926 to her partner of the time, the American photographer Edward Weston:

“I am forever struggling to mould life according to my temperament and needs. In other words, I put too much art in my life - and consequently I have not much left to give to art.”

And yet, she has given to art so much: her own photography for a start (for instance her photographical study of the Zapotec population in Mexican state of Oaxaca), but it was also she who introduced Frida Kahlo to Diego Rivera,** and when she died, Pablo Neruda gifted us with these beautiful verses on his “hermana”, with which I shall sign off.

Tina Modotti, hermana, no duermes, no, no duermes:

talvez tu corazón oye crecer la rosa

de ayer, la última rosa de ayer, la nueva rosa.

Descansa dulcemente, hermana.

Tina Modotti, o sister of mine, you do not sleep, no, you do not sleep,

perhaps your heart can hear yesterday’s rose grow,

yesterday’s last rose, the new rose,

Rest gently, o sister of mine.

Pablo Neruda, extract from Tina Modotta ha muerto, 1942

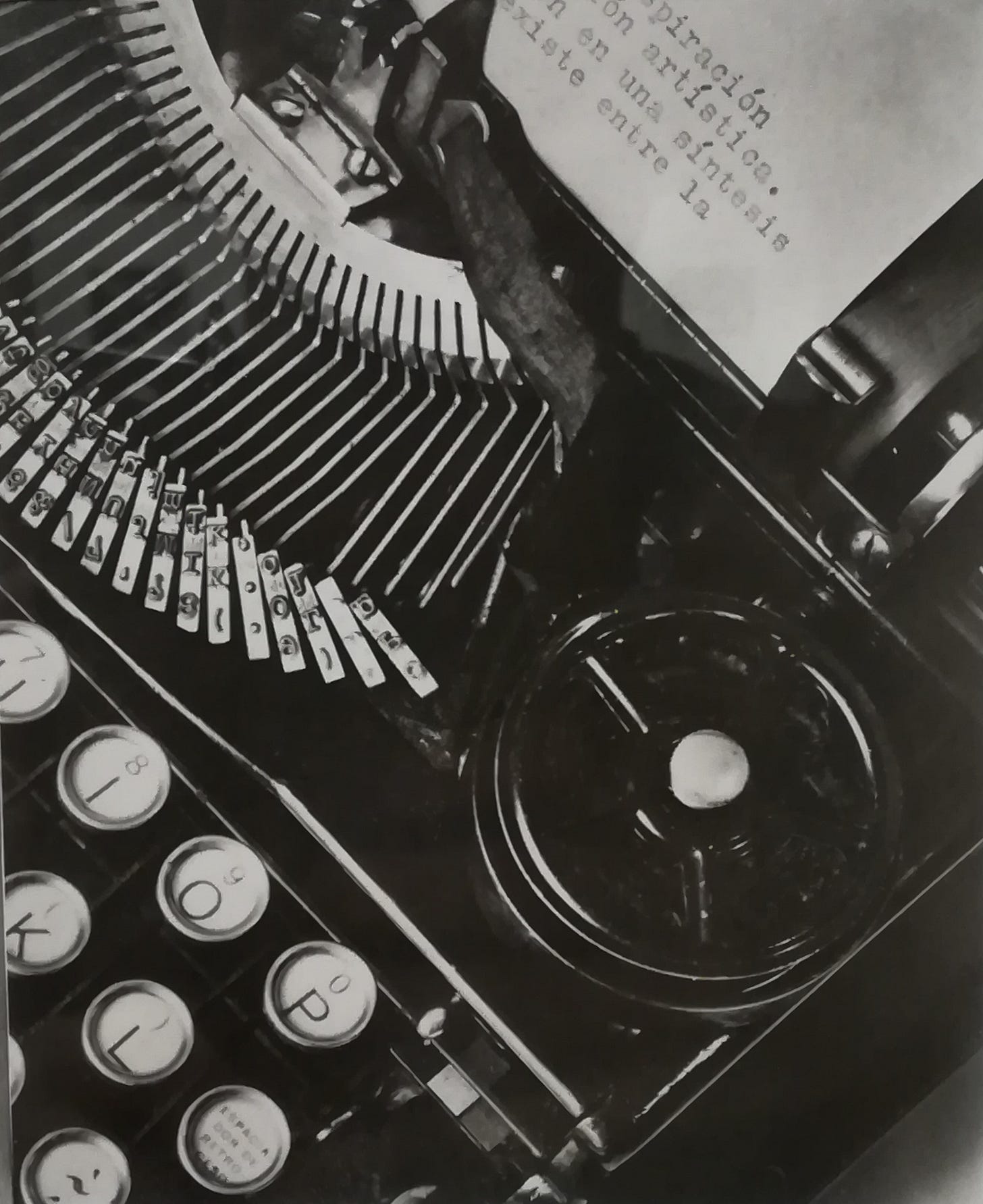

Tina Modotti, The Typewriter of Julio Antonio Mella (La Técnica), Mexico, 1928.

(***Another romantic couple of artists! Although Diego Rivera overpowered her during their life, a twist of fate - and marketing - has raised Frida Kahlo as an icon. Unlike her sorry partner.)

Do you enjoy reading me ? Please consider supporting the project on Tipee, with a one-off or monthly contribution. You will get extra news on the project along the way, and for all contributions of 7€ or more, you will receive a special Peripatetic Postcard, from one the museums I visit. Three are already one their way !

This is a gorgeous post, full of wonderful art and fascinating stories.

Super interesting ! Thank you for this original perspective on paintings wich give us a renewed look on paintings :))