11. Creation instead of destruction

On conflict and peace and how artwork ends up where it does

“Be a prince of peace, put action in the place of word, humility in the place of victoriousness, truth instead of lies, creation instead of destruction.”

“Sei Friedensfürst, setze an die Stelle des Wortes die Tat, Demut an die Stelle der Siegereitelkeit, Wahrheit anstatt Lüge, Aufbau anstatt Zerstörung.”

Heinrich Vogeler, Das Märchen vom lieben Gott (January 1918)

In the Gospel according to Saint Mathew, shortly after the birth of Christ, an angel visits Joseph in his dreams and tells him to flee with Mary and the newborn baby into Egypt, to escape King Herod’s persecution. Jesus’ life starts with a departure, with flight, with an experience of forced travel.

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, Flight into Egypt, ca. 1645-1650, Musei di Strada Nuova - Palazzo Bianco, Genoa.

It is this moment that the Spanish painter Bartolomé Esteban Murillo depicts in his Flight into Egypt (ca. 1645-1650). He offers a naturalistic and intimist interpretation of the Gospel episode, presenting the Holy Family as a humble peasant family in transit on a country lane. Despite the urgency of the situation, a certain calmness emanates from the painting, and Mary appears absorbed in the contemplation of her son, trusting in divine mercy. Joseph, on the other hand, appears slightly anguished, leaning forward in movement, urging the family along. They are, after all, fleeing.

This painting now hangs in the Palazzo Bianco, one of the buildings of the Musei di Strada Nuova, in Genoa. Initially, though, it was made for the church of the Merced Calzada in Seville, but was requisitioned by Marshal Soult in 1810, during the French occupation of Spain, and ended up in France, like many works by Spanish masters. By the mid-century, these works started appearing on the art market, and many were bought by Raffaele De Ferrari, Duke of Galliera - including, in 1852, Murillo’s Flight into Egypt. These acquisitions were destined to embellish the rooms of the Duke’s luxurious Parisian residence, the Hôtel Matignon (now the official residence of the French Prime Minister), but were later left as a legacy from the Duchess of Galliera to the city of Genoa.

And so, just as Mary and Joseph were led onto a path of migration, the painting The Flight into Egypt itself was forced on a long journey caused by military conflict, from Spain to France to Italy. This might remind you of the San Marco horses I wrote about - they were also looted, by the Venetians in 1204 and then by Napoleon in 1797. Now, they have been returned to La Serenissima…

***

A few weeks later, after travelling through Slovenia, Hungary, and Romania, I was back in Western Europe. In Berlin, to be exact, where I met the Romanian artist and curator Luana Cloșcǎ, and visited the Galeria Plan B. Just before leaving, I squeezed in a visit to the Neue Nationalgalerie. Housed in a monumental building designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, an architect regarded as one of the pioneers of modernist architecture, the museum presents in a thematic exhibition a selection of art from its collections from 1900 to 1945, which reflects the important historical and artistic events of the period.

Covering a period marked by colonialism, National Socialism, two World Wars, and the Holocaust, the museum must tackle an uneasy history, to say the least. The curators chose the path of transparency and honesty (I doubt anyone would argue that this isn’t a generally commendable one). A particularly sensitive topic is the National Socialists’ relation to art.

There are, of course, the works of art decried as “entartet”, or degenerate - anything modernist, Jewish, Communist or generally not fitting with the party’s understanding of “Germanness”, although the criteria were hazy at best. For instance, the sculptor Rudolf Belling was represented in both the Entartete Kunst exhibition and the Große Deutsche Kunstaustellung (Great German Art Exhibition), which aimed at defining the National Socialist artistic ideal. This period left gaping holes in German museums and art in general. Under National Socialism, approximately 20,000 works of art were removed from more than 100 German museums. They were either sold to other countries or destroyed. The National Gallery lost more than 500 works, nearly half of which ended up abroad.

There are, also, the works of art deemed worthy in the National Socialist’s conception of art. Adolf Hitler had a plan to build a special art museum in Linz, which would display art bought, confiscated or stolen by the Nazis throughout Europe, and turn Linz into one of the greatest artistic capitals of the continent. During this time, the art historian Erhard Göpel was assigned to the “Sonderauftrag Linz” (Linz Special Commission). Through his expertise in the field of Dutch Old Masters, he was responsible for the occupied Dutch regions, France and Belgium. Although he actively participated in National Socialist acquisitions of looted art, focusing on Jewish property that could be acquired below value or expropriated, he is said to have also protected many Jews at the same time, employing about 90 on his staff, declaring them indispensable.

Furthermore, he smuggled Max Beckmann’s art - categorised as entartet - back to Germany during the 1940s. The artist had left the country in 1937 and was living in Amsterdam, and both men stayed in contact over the years. Göpel’s portrait by Beckmann now hangs in the exhibition. It is, as the wall text reads, a “discomforting portrait”.

Max Beckmann, Portrait of Erhard Göpel, 1944, Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin.

***

It is not only German museums which were scarred by National Socialism. In Italy, too, museums bore the traces of these wounds, many fine works of Italian art having been transported to Germany during this period. The art historian Rodolfo Siverio - dubbed the “007 of the art world” - is to thank that most of the artworks were eventually returned after the war. Joining the Italian secret service, he set out to Berlin in 1938 to gather information on the Nazi regime, under the guise of a scholarship in art history. Towards the end of the war, he sided with the anti-fascist front, and from 1943 onwards, he carefully monitored the activities of the “Kunstschutz”, a body originally created to protect cultural heritage during the war but that had shifted to shipping a large number of artworks from Italy to Germany.

Thanks to his reputation for resistance work and his careful monitoring of the art leaving Italy, Siviero was appointed after the war to direct a diplomatic mission to establish their return. Thanks to his rigor and meticulousness, countless works of art now hang once again in Italian museums, such as this Nativity (ca. 1510-1520), returned to Italy in 1954 and assigned to the Uffizi Gallery in 1988. If European collections have been wounded by conflict, they are, evidently, able to heal, leaving scars which act as valuable historical testimonies.

Unknown painter, Nativity, ca. 1510-1520, Uffizi Gallery, Florence.

***

After the historical turmoil of the Neue Nationalgalerie, and the urban tumult of a European capital like Berlin, I welcomed the peace and quiet I found in Worpswede, a small village near Bremen, in Lower Saxony, and an artists’ colony at the beginning of the 20th century. Arriving after nightfall on a Sunday evening, I made my way from the bus stop in the dark along the “Schluh”, where I was greeted by Harro Jenss - a blinking flashlight in the dead of night until he came closer and we could make out each other’s faces. He led me to the “Haus Im Schluh”, a traditional Lower Saxon thatched house, up to the first floor and into the “Blaues Zimmer”, a cozy room decorated by Martha Vogeler, the first wife of the artist Heinrich Vogeler.

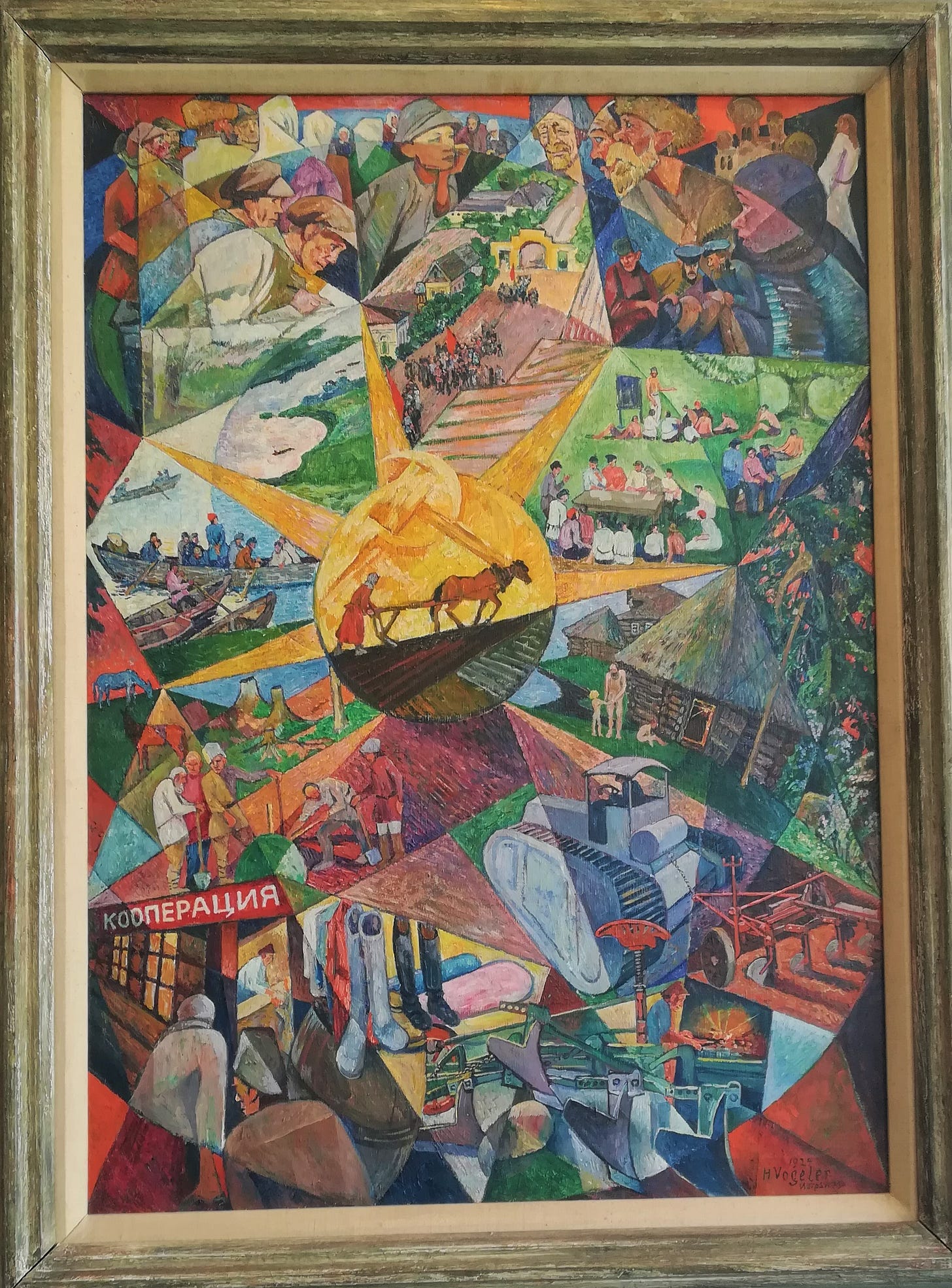

I had followed him figuratively from the Neue Nationalgalerie, where several of his later works, his so-called “Komplexbilder” (Complex Images) were exhibited. Dividing the image’s surface into different sections which he filled with land and cityscapes, communist imagery, and scenes of work and leisure, he seeks to convey a visual synthesis of life in Soviet society. Coming to Worpswede was like going back in time - the time before the First World War, where he was still a renowned Art Nouveau designer. He lived in the Barkenhoff cottage with his muse and wife Martha and their three children, and founded with his brother in 1908 a workshop which produced his designs for furniture, cutlery, and other household objects.

Heinrich Vogeler, Student's’ Work Effort During the Summer, 1924, Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin.

But the idyll progressively unravelled amidst growing tensions between the artists of the colony and the breakdown of his marriage. He volunteered for military service in 1914 and was sent to the eastern front in 1915. Initially working as an artist for the army, depicting life on the front and painting the portraits of officers, he became progressively disillusioned with the war. This marked a turning point in his life, and by 1918, he was a convinced pacifist and communist, writing in 1918 his famous peace appeal to the Kaiser Wilhem II, Das Märchen vom lieben Gott (The Fable of the dear Lord) - for which he was luckily not shot, but shortly institutionalised. In 1923, he made his first trip to the still young Soviet Union, and in subsequent years, he travelled there extensively, eventually emigrating to Russia in 1931.

Thinking of these scars which art collections bear, his letter still rings true today, carrying a plea for, as he puts it : “creation instead of destruction.”